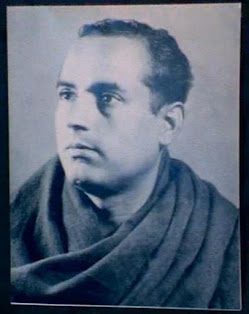

Devkota in Translation

Mahesh Paudyal

Of all the Nepali men of letters, Devkota stands out as one of the first writers to feel and air the need for translating Nepali literature into different world languages. His Tashkent address, delivered as early as in 1958, was basically rooted in explicating this dire need for translation, which, to him, was the most fundamental prerequisite for taking Nepali literature to the global front. He himself lived up to his words by taking two approaches: himself sitting down to translate some of his works previously written in Nepali, and translating some of the finest works of his contemporaries like Lekhanath Paudyal, Siddhicharan Shrestha and Shyamdas Vaishnav. His own works Shakuntal and “The Lunatic”, besides a series of poems published in a bilingual edition of Indreni showcase Devkota’s calibre as a translator par excellence.

Translation was one of the key strategies

through which Devkota’s fame crossed the limits of Nepali language and passed

over to the International audience. Of the earliest most important translations,

mention maybe made of those done by David Rubin and Michael Hutt, to be

followed by others later. Rubin’s translation made Devkota known to the

American Academic and literary world vindicated by the praised he received,

albeit sparingly, from the American readership. Making a comment on a translation

of Devkota by David Rubin and published by the University of California, its

editor Allen Thrasher regards Devkota as a true artist contributing to the

development of Nepali literature. He

writes, “Though the history of Nepali literature is more than five hundred

years old, its true development took pace only in the twentieth century and

Laxmi Prasad Devkota is the greatest writer of this era. He developed a huge

archive of writing in different genres, and was influenced by English romantic

poets. Like them, Devkota gave priority to romanticism, lucidity and

emotionality.” In its description of the curriculum on Asian Languages, University of Cornel mentions

that writes like Laxmi Prasad Devkota, Bhanubhakta Acharya and Lekhanath

Paudyal established Nepali language as a literary language.

Translating

Devkota is quite a feat. He is not easily picked up by translators. His overt

rootedness in Nepali lifestyle requires a translator to be equally proficient

in both source and target languages and cultures and such people are not many.

As a result, many translators do not dare to take up Devkota under their

project, and I am one of them. The few that have seriously dealt with him have

reported of untellable rewards the very task gives. Pallav Ranjan, expressing

his experience of translating “Yatri” mentions that understanding the central

theme of Devkota’s writing is like seeing vapour in the fog or seeing the light

of thousands of fireflies at a time.

A section of Nepali literature published

by JNUF Documentation Letter mentions Devkota, together with Guru Prasad

Mainali and BP Koirala as one of the greatest writers of the pre-revolutionary

period and the credit goes to translation and original delivery in English. In

a BBC debate conducted in October 2000, Devkota has been ranked along with

Haribansha Rai Bachhan, Mukraj Anand and Michel Ondaatje as one the exponential

writers in Asia, who has delivered excellent works in English

Since

Devkota stands out as the most renowned Nepali writer so far, many translators

have tried their hands in rendering him into different languages. We have read

several circulations of the poet’s most famous poem “The Lunatic”. Besides some

less-famous renderings, those in wide circulations are Michael Hutt’s and Rubin’s

translation. Among Nepali writers, Taranath Sharma has tried one, in his own

idiosyncratic ways of language use. I have the information that this work has

also been translated into Bengali as “Jorur Bondhu Ami Pagol” by a Nepali diplomat Sushil Kumar

Lamsal in Bangladesh.

Thus

Ludmila Aganina got some of Devkota’s poems in Russian. Dr. Janagam Chauhan, in

one of his articles mentions that Aganina gave one of the poems to Russian poet

Jheleznov, who translated it into Russian. Including this poem, a collection of

Nepali poems entitled Poems of Nepali Poets was published in 1962 in Russian

for the first time. The collection was edited by Aganina herself. Devkota’s

story “Teej” was also translated into Russian by Aganina and was included in a

collection of Nepali stories Love of

Mother (1962). “In Moscow” and “Blue Are the Mountains” were among the

poems published in Russian translation. Ludmila Aganina and Krishna Prakash

Shrestha took initiatives and, as a result, Selected Works of L.P. Devkota was published

in the following year. This has proved to be an important event in augmenting

Nepal-Russia literary relations after the collapse of Soviet Union.

Devkota’s

book The Lunatic and Other Poems

includes thirty poems translated by the poet himself, dealing with “variety of

themes, however, to be more specific, the concept of ‘Nature’, sharp satire on

socio-political situation and caste based discrimination, love and memory, desire

for change/revolution, pride of nationality and importance of food formulate

the major themes of these poems”

Himalayan Voices, an Introduction

to Modern Nepali Literature, edited and translated by Michael

Hutt contains in translation some of Devkota’s poems like “Sleeping Porter,” “Prayer

on a Clear Morning in the Month of Magh,” “Mad”, “Like Nothing into Nothing”

and extracts from Muna Madan.

Selected Nepali Poems, translated and edited by Taranath Sharma and published

by Jiba Lamichhane contains five poems by Devkota, which include “A crackpot I

am”, “Bolt”, “My Lord, Make Me a Sheep”, “To the Morning Sky” and “Why Does a

Tiger Eat Its Cubs?”

The Himalayan

Bard, published by NRNA contains a poem “Make Me a Sheep, O God,’ translated by

Bhuvan Thapaliya from the poet’s original, “Prabhu Malai Bheda Banaideu.” A comparative reading of this short rendering

(extract) by a young practitioner, to me, sounds far more simple, accurate and

poetic that Taranath Sharma’s prosaic rendering.

Recently,

Muna Madan has been rendered into

Chinese language by a Chinese poet Liu Jian. My linguistic limitations do not

allow me to make any comment on the Chinese version, but my personal discussion

with the translated during my recent visit to Beijing (I can pass his numbers

and email to you if you need) has convinced me that he was impressed with the

content of the work and is interested to take up newer projects in this line.

I

also have the information that by involving the students of MPhil, the Central

Department of English, TU has got some of Devkota’s stories translated. When it

gets published, it shall add yet another laurel towards internationalising

Devkota’s works.

As

a translator, I haven’t tried my hand in many of Devkota’s works. Some of my

translations of his poems published online and in print over the past few years

include his poems “Give Me Rice,” “Lentils and the Green Stalks”, “The Latch”, “Freedom Is But Humanity”, “Asia”, “Yes It’s

Bullet” and “The Traveller”.

Now

a passing note on my own experience of translating Devkota. Devkota’s short

poems are comparatively easier that his epics or prose pieces. Unlike his epics

that are overtly rooted in Nepali culture and mythological tradition with a

preponderant of local images and allusions, his shorter poems rest on a

tapestry of universal images and themes. In that case, the shirt, which

inevitably occurs during the transition between two remote languages and

cultures like Nepali and English remains minimum. The best strategy is not to

render the units, but to render the text. In other words, textual render is

more favourable that formal rendering in case of Devkota. For, in his short

poems, more than the very structure of form of the text, his message is

important. The biggest potential of taking Devkota abroad too, in my personal

opinion, lies in attempting to render his short poems and prose pieces rather

than his epics. In spite of their lofty subject, Devkota’s epics like Muna Madan have prevailed over the years

due mainly to their musicality and folk meter which are badly thwarted in

translation. I maybe wrong, but the English rendering of Muna Madan could not do much justice to the poet’s masterpiece and

it failed to establish itself as one of the most popular picks for Nepali

readers. I am of the opinion that if his epics are to be rendered, it should be

done by Nepali speakers proficient in English under the supervision of learned

scholars so that the puns are not misinterpreted, cultural allusions are not

thwarted, the musicality is aptly replaces and the very heart of Nepaliness is

kept intact.

Comments

Post a Comment